Whiter Skin for Sale: South Korea’s Glutathione Dilemma

Popularity of Skin Whitening Sparks Debate in South Korea

by Morgan Norris

As the multibillion-dollar K-pop and K-beauty industry continues to shape beauty ideals, glutathione has gained popularity on social media as a sought-after skin-whitening solution. Marketed as a shortcut to luminous skin, the antioxidant’s rise is entangled with dialogue surrounding Korea’s motivations for whitening skin.

In countries where higher doses are needed to achieve visible whitening effects, the drug’s unregulated use poses serious health risks, obscuring its original medical purpose as a liver-supporting antioxidant.

This reporting project raises questions about safety, identity, and the cost of beauty.

I walked into Olive Young, dubbed the “Sephora of Korea” due to its popularity as a significant health and beauty retailer and asked which products they would recommend for me to use to whiten my skin. After visiting several Olive Young stores in the Gangnam, Mapo, Cheongdam, Apgujeong, Yongsan, Yeongdeungpo, Jung, Myeongdong and Yeongdeungpo districts, I noticed that they all had one recommended product in common – glutathione.

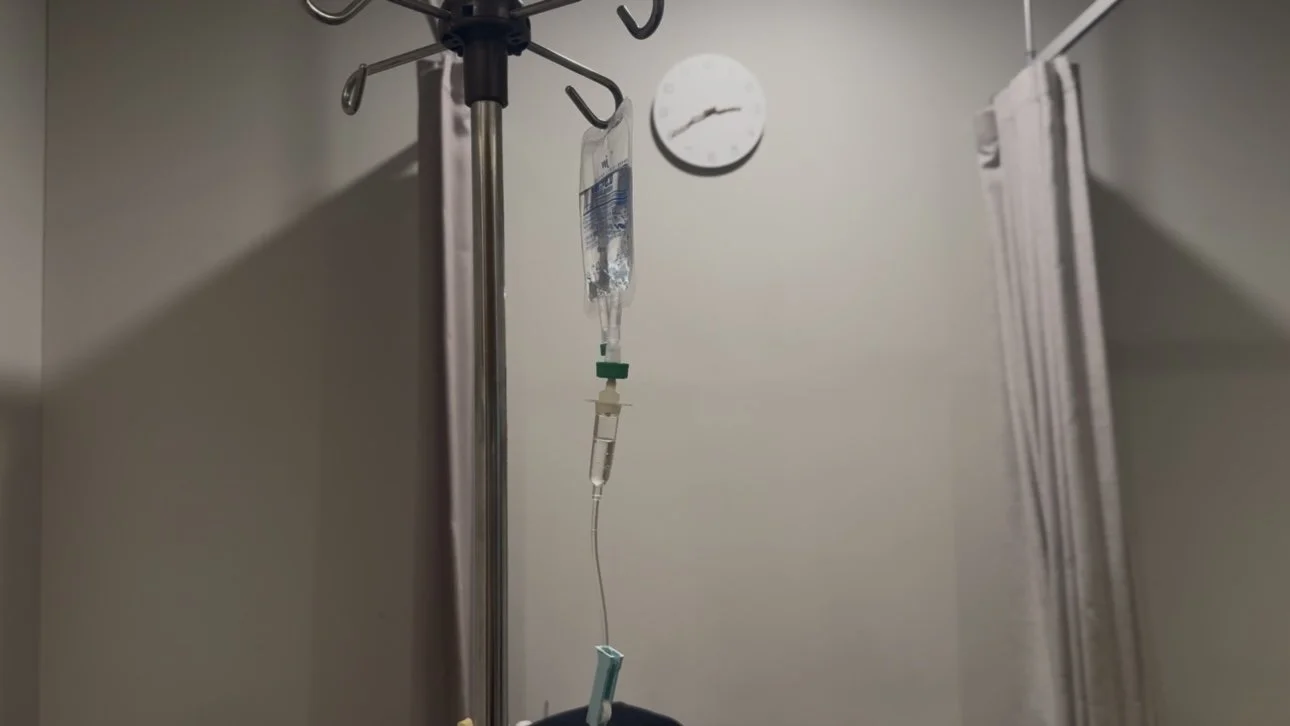

Intravenous, oral and topical glutathione gained popularity in the 2010s due to aggressive marketing, influencer endorsements and social media. Olivia Choi, the founder of Seoul Beauty Global, used to get glutathione routinely injected into her skin.

“Everyone gets it, to be honest. Most just go during their lunch break instead of eating,” said Choi. “It only takes an hour, and I felt so rejuvenated.”

She has now stopped taking the antioxidant.

“Because I was afraid of getting addicted,” said Choi. “Some people do, and a lot of people take it for the whitening purpose.”

Korean beauty standards have a few common features: double eyelids, a V-shaped jawline and a nose with a high bridge. The most mentioned is white skin.

“On a daily basis, people (in Korea) are trying to be whiter,” said Choi. “You’ll see umbrellas, sunscreen, etc.”

During conversations with over three dozen average Koreans and foreigners, they reported knowing glutathione as a “whitening drip” (미백주사, mibaek jusa).

How did its reputation for skin whitening spread so far? Social media.

insert (Photo 8 SKP): Picture of employees at Seoul Beauty Global collecting data about K-beauty on social media, where they often run into the “whitening” injection. Taken by Morgan Norris

“They name it Cinderella, Snow White, Beyonce for marketing purposes,” said Choi. “It’s so cheap, too. Only 30-100 bucks.”

With a quick search for glutathione drip, among all the nicknames, the main reputation is associated with the term “IU drip.” IU is a South Korean pop star who is known as “South Korea’s little sister.” She became the face of the glutathione drip due to her infamous before-and-after photos, which showcased her once-tan skin and now-fair complexion. There are countless videos of beauty influencers promoting the whitening shots using the artists’ pictures on social media.

“She was Korea’s shining star and one of the first idols who popularized the Korean beauty standard,” said Quinn Lin, a Chinese-American former K-pop trainee.

In 2022, Lin was recruited by DR Music Entertainment to replace a member of Black Swan. She began taking the glutathione drip and using glutathione soap after seeing the “IU drip” trend in K-pop fan spaces, such as Amino Apps and Instagram.

“I immediately saw a change,” said Lin. “Everyone used to say I look Filipino, but when I started using it consistently, I got so pale that I couldn’t even be out in the sun long anymore, or it would start to burn.”

Lin argues that K-pop idols are crafted to embody Korea’s ideal beauty image, serving as aspirational figures who shape global perceptions and drive tourism.

“I wanted to look the way that everybody idealized,” she said. “I used whitening sunscreen, nail growth oils, and double eyelid tape to make my eyes bigger and did face massages to make my face thinner.”

She even demonstrated how lighting and apps contribute to the “whitewashing” trend.

“I have a ring light that I use, and it purposely makes me appear whiter,” Lin said as she turned her ring light on and off. “Idols have lighting, use lighter foundations and edit their photos.”

Elise Hu, the author of Flawless, wrote about Hallyu, the word for ‘Korean wave’ symbolizing the spread of Korean entertainment from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s.

“As k-film, k-drama and k-pop proliferated around the world, so did the aspirational look of these K-idols,” Hu told Forbes. “While K-beauty practices are a key part of the Hallyu wave, beauty is often thought of as a soft topic, something that's relegated to women's magazines. Yet how we show up in the world is deeply embedded in so many political, social, and economic systems.”

If you search “kpop whitewash” on any social media platform, tons of videos will show idols who are tanner in real life than they appear, with IV glutathione, among stage lights and filters, being assumed as the cause.

Board-certified dermatologists, however, condemn its reputation.

GLUTATHIONE’S TRUE IDENTITY

“If we use glutathione as needed, it’s a great antioxidant,” said Dr. JiYoun Park, a Korean board-certified dermatologist and founder of the Ozhean Skin and Plastic Surgery Network. “If someone is using it saying, ‘I want to whiten my skin’...that’s not recommended.”

Glutathione (GSH) is a tripeptide made of glycine, cysteine and glutamic acid. The antioxidant is produced in every cell within your body, and high concentrations are found in your liver. A deficiency of glutathione puts the cell at risk for oxidative damage. It is also used for detoxifying the liver and other cell-balancing purposes in various organs.

Its antimelanogenic properties caused the media to over-market the antioxidant as a skin whitening agent. The three amino acids affect the production of eumelanin (black/brown pigment) and pheomelanin (red/yellow pigment). Glutathione can shift melanogenesis towards pheomelanin, potentially leading to lighter skin or hair and can also reduce eumelanin production by inhibiting tyrosinase, an enzyme crucial for melanin synthesis. However, the effect is minimal. Whiter skin is only a side effect evident after multiple intravenous treatments.

“Theoretically, glutathione can convert a dark melanin pigmentation into a brighter melanin,” said Dr. Park. “But doing it too much for the whitening effects, like once every 2-3 days, problems can arise in renal functioning, or even put pressure on your nervous system.”

According to the World Health Organization, there are no universally accepted dosage guidelines. Biologically, high glutathione levels suppress melanin production, but the individual amino acids can interact in conflicting ways within the body. Glutamate may overstimulate, triggering headaches and irritability. Cysteine can become pro-inflammatory, causing breathing issues and skin reactions. Glycine, usually protective, may paradoxically increase oxidative stress. At worst, complications could lead to Stevens-Johnson syndrome or kidney failure.

Still, the practice of using glutathione for skin whitening persists in communities around the world, with IV glutathione being administered locally and shipped internationally. Since the Philippines Food and Drug Administration, the U.K., Singapore, Malaysia, and the U.S. have either banned the sale of intravenous glutathione or issued cautionary statements warning of liver damage, severe allergic reactions, and the absence of safety benchmarks, South Korea has become the hub for the treatment.

“WHITENING” IN KOREA vs. “WHITENING” GLOBALLY

Whiteness in the Korean language is 미백 (mibaek). But what is considered ‘whitening’ can be interchanged with ‘brightening.’ There is no direct word to translate ‘brightening’ from English to Korean, so people use ‘whitening’ (미백, mibaek).

“It can be misconstrued,” said Tony Medina, CEO of Seoul Guide Medical. “I can easily see how social media can take this and turn it into an issue.”

The comments under videos promoting glutathione as a skin whitener are filled with arguments between Asian and global users about why wanting whiter skin is problematic to the West and normal to the East.

“The whole goal for Koreans is to be even-toned, so they just go lighter instead of darker,” said Medina. “Koreans say whiter because their skin tone is obviously closer to the color white.”

The Seoul Guide Medical CEO emphasized that sellers of IV glutathione use these mistranslations to successfully market the antioxidant as a skin whitener, which can be harmful to users. This has led major regulatory agencies, such as the FDA, to ban the use of the antioxidant.

“I remember reading an article a long time ago about why thread lifting was banned in America. First, it was approved, then it was banned because there were several cases of it going wrong. Then it was approved again,” said Medina. “For glutathione, it is more on the political side, and the systems are not good enough in those countries to know how to use it properly.”

MISUNDERSTANDING CAUSED MISUSE

“If glutathione were not that popular and all the clinics and practitioners followed the guidelines within protocol in other countries, would the FDA ban glutathione? No,” said Julie Rhee, a Korean-American pharmacist with a doctorate in pharmaceutical studies.

Rhee founded a government-certified medical tourism agency in Korea and her bicultural upbringing and scientific expertise give her a unique edge in navigating cultural nuances and evaluating treatments, such as glutathione.

“If it's not marketed as a whitening effect, people won’t get the treatment because detoxifying your liver is not good enough for sales. This is about a balance between efficacy, safety, and business,” she said.

One woman in the Philippines suffered acute kidney failure after 3 years of weekly glutathione injections, according to Channel Asia Network, in 2018. 69 patients suffered from complications due to IV glutathione use.

Glutathione injections are marketed as “Korean Gluta Drips” overseas, making South Korea the epicenter of skin whitening for beauty gurus around the world. But, according to Korean natives, “whitening” is a term that has been historically misunderstood and used as a way to promote white skin racially.

“There is a misconception within the question– ‘Why are Korean people so obsessed with pale and white skin?’” said Rhee.

THE HISTORY BEHIND THE ONLINE MISCONCEPTION

“White skin is so valuable there because it is ingrained into people's psyche over five or six centuries of thinking about spending time inside (away from the sun), reading a book, studying, and preparing for the national exam is of most prestige,” said Professor Gooyoung Kim at Cheyney University, the first HBCU in America.

During the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1897), according to Asia Society, women were taught to prioritize samhong (삼홍;三紅), samheuk (삼흑;三黑),= and sambaek (삼백;三白). Samhong translates to the three reds: the redness of cheeks, lips and peachy fingernails. Samheuk translates to the three blacks: charcoal-black pupils, eyebrows and hair. Lastly, sambaek translates to the three whites: white teeth, white eyes, and white skin.

To whiten their skin, Joseon women used rice powder and herbal pastes, similar to the whitening sunscreens and foundations used today.

“Americans value going out and adventure, so people with status over here have tan skin as a sign of status,” said Kim. “But in South Korea, going back to Confucianism, it’s the opposite.”

Historically, however, Westerners were not considered “white” during the Korean War.

“We thought of the people from the Netherlands back then as ‘red’ which meant their faces were pinkish-red to us,” said Dr. Jimin Lee, the department head of translation at Keimyung University. “It never was about ‘admiration,’ of the West as much as being a symbol of wealth.”

SOCIAL MEDIA ARGUES

A recent incident that went viral is a Korean reality dating show titled “Single’s Inferno.” As the singles were talking about each other’s best qualities, the male participants kept raving about pale skin, saying, “She is so white. My first impression of her was that she is very white, so purely white. I like people with white skin.”

There was an immediate divide among online viewers.

“Watching #SinglesInferno and their obsession with 'pure white' skin is a bit unsettling,” wrote one global user.

Another global user wrote, “It’s so weird watching single inferno and hearing them talk about skin colour, light skin = pure and white .. difference in culture I guess but wondering what they think about black skin lol #SinglesInferno #singleinfernonetflix.”

Korean users, however, seemed offended by the assumptions and misunderstandings.

“Wow, they don’t respect personal preferences,” wrote one Korean viewer. Another said, “White skin has been a standard for beauty for ages in our country. What’s this about? What ‘white people’?”

“A lot of the controversy could have been saved if anyone cared about Western audiences and their issue,” said another Korean viewer.

Posts promoting the “whitewashing” trend on social media, whether it’s idols, K-dramas, or AI apps, are filled with comments from international fans assuming South Korea has a culture of wanting to be white.

“Koreans are very misunderstood when it comes to this issue,” said Shin Dainn, a beauty influencer on TikTok. “It can be very frustrating.”

Dainn, @haroo_dainn on TikTok, posted a video with the caption “How to make my skin white,” using photos of IU and before-and-after photos of once-tan skin to her current pale complexion. In the video, she recommends taking oral glutathione supplements. She received around 3,000 likes, but the comments were filled with users arguing about glutathione and skin whitening.

“Koreans don't even care that much,” she said. “All the foreigners were saying glutathione wasn't healthy and going back and forth about our preferences.”

The beauty influencer believes others shouldn’t judge Korea’s preference for lighter skin or view it as something negative. She believes race has nothing to do with controversy.

“I feel taken aback whenever race gets brought up (in regards to this topic), because it’s not about that at all,” she said. “It’s not like in America or other countries where an Asian person can say they ‘want to be White’...It’s truly just between other Koreans, where we think whiter, brighter skin is more attractive because that’s what our noble ancestors had.”

PROGRESS CONCERNING COLORISM WITHIN KOREA

Under the bright lights and in front of the full-length mirror, Leah Lee expresses herself with sentiments of nostalgia and finality, as these are the last few months she’ll spend time dancing on the gray tiles.

“Daegu is very conservative for me, which is why the younger generation has a hard time with changing things (societal norms) here,” said the 33-year-old choreographer. “Korea has a lot of invisible rules in society.”

Lee believes women should not have to abide by societal expectations to work in male-dominated fields and corporate settings, which often come with an inevitable pressure to conform to traditional standards of appearance.

“The first time someone called me beautiful was in Canada,” said Lee. “Their mindset is more in line with gender equality. In this society, beauty is what looks best, but beauty is more diverse there.”

Although she felt happiest in Canada, Lee decided to start her company, Everybody Dance (모두의 춤), in Daegu, South Korea.

“My Korean identity is Youngrae Lee,” she said. “I did all my schooling here, you know? I came back to find myself.”

She soon regretted this business decision.

“There’s definitely a glass ceiling. If I use the same photos (for marketing) in Korea that I used in Canada, I will get less business,” Lee said. “In Canada, they love the most raw, unedited version of yourself, especially for performing arts jobs. In Korea, every job for women wants every inch of your photo to be ‘tuned,’ like a work of art. I don’t want to get used to that. So, I’m leaving Korea and going back to Canada.”

Leah Lee will be permanently closing Korea’s location of Everybody Dance (모두의 춤) in December.

A glass ceiling (유리 천장) is a metaphor used to represent an invisible barrier that prevents women in Korea from advancing beyond a certain level in a hierarchy. Feminists first used the metaphor in reference to barriers in the careers of high-achieving women, which is often referred to as the 4B movement.

“You heard of ‘Tal-corset’ (탈코르셋), right?” said Professor Hyun Mee Kim at Yonsei University. “The idea is to go against any feminism required by the constraints of the patriarchy.”

“Escape the Corset” is a movement involving women who reject Korea’s standards of beauty and societal pressures to conform. Most advertisements feature Korean women with white skin, long hair, extensive makeup, and form-fitting clothes.

“To receive better treatment in the workplace, women may get si-sul (시술) like skin whitening, because men are in charge,” said Kim.

Job postings often require profile pictures on resumes, and those with lighter skin tones usually have an advantage. Newscasters, in particular, must maintain an ideal image of Korean beauty on television.

“Since my job is being on TV, the same demands for me don’t apply to male anchors,” said Hyangwon Lee, an anchor for TBS 8. “The preference for white skin, even just among those in my circle, is notably high. There’s even ‘white tanning’ and ‘skin whitening’ makeup products.”

Although skin whitening remains a demanding market, people who prefer tanned skin are growing in number and are engaging in weight training to develop more muscular bodies are also entering the physique field.

Scarlet Park, a physique model, pointed to her skin and said, “This is considered really dark. Now that I'm doing these ‘body profile’ photoshoots and exercising, I have to tan, you know? So I kind of gave up on having white skin and decided to live with my current skin tone.”

White skin has shifted from a beauty standard to a loose preference. South Korea is starting to consider darker skin tones beautiful.

“The beauty standard, as it pertains to women, is changing, and people are starting to see that ‘Being active can also be feminine,’” said Park. “Because of this, naturally, this idea that ‘only white skin is beautiful’ shifted to ‘tan skin can also be healthy and beautiful.’”

BEAUTY BY KOREA, NOT THE WORLD

This global misunderstanding of the outdated beauty standard, fueled by media oversimplification and commercial opportunism, has turned Korea’s nuanced beauty ideals into a marketable myth, repackaging cultural preferences as racial aspiration to sell products like the so-called “IU injection,” which is essentially glutathione, an antioxidant.

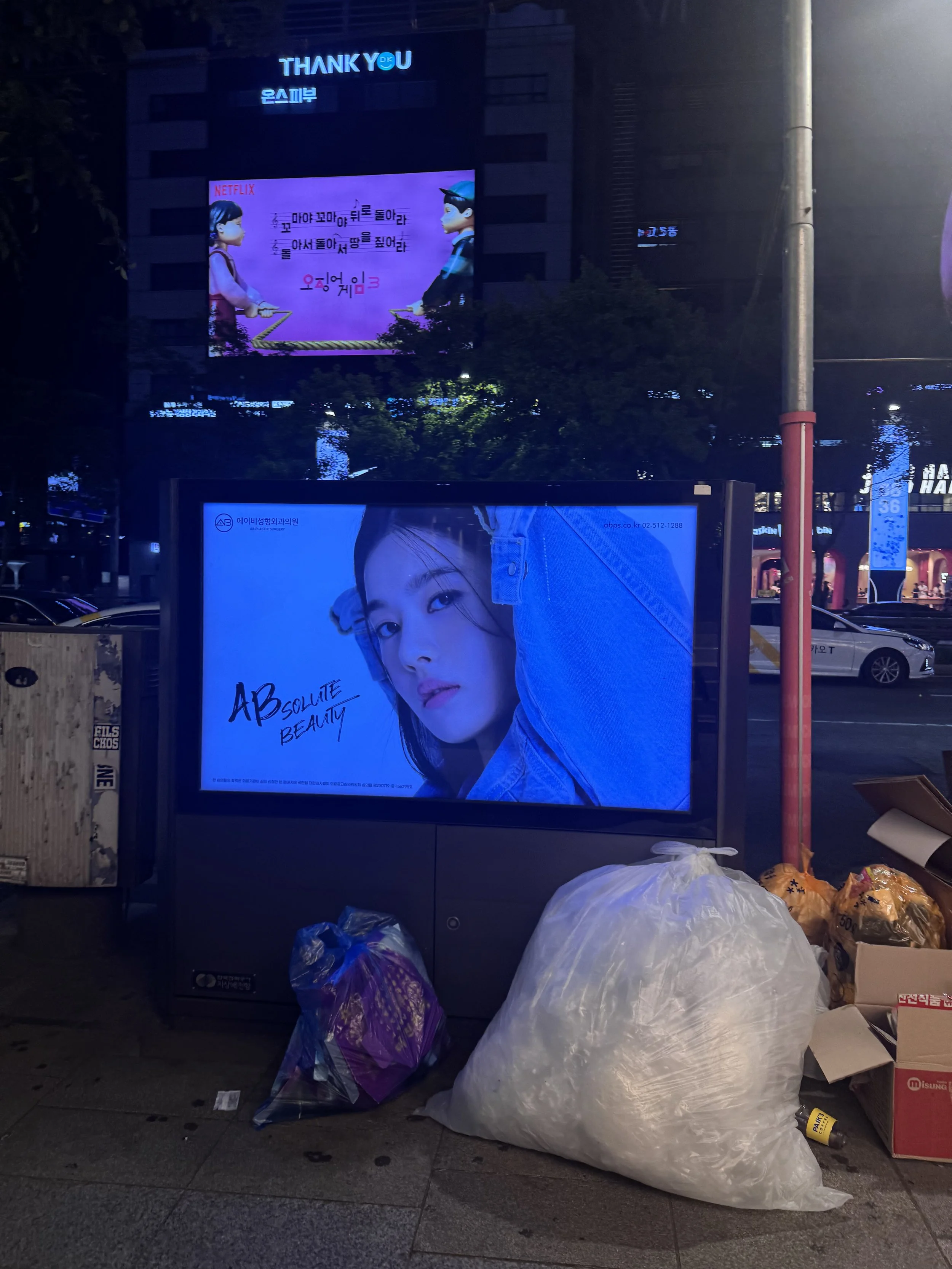

“I’m sitting in Gangnam right now, and so many advertisements about glutathione as a skin whitener surround us,” said a Korean woman, who requested to go by “Julia.” “At some point, you think it’s normal. I think that’s the problem.”

In the meantime, South Korea is navigating the shifting landscape of feminism and striving toward a future where all skin tones are considered beautiful.

“People in Korea want to change,” said Julia. “Since there are lots of immigrants and foreigners starting to live here, we should change that mindset. It may take time, but I hope we do.”